Some bars make you feel like a stranger in someone’s living room. Every time someone walks into Swede’s, there’s a chorus of familiarity. “Ah Bob, up to no good huh?” “Here comes trouble.” Bob staggers in with his cane. He was the topic of some gossip earlier, something about his Life Alert going off and everyone was worried but it turns out he just pushed it against a counter.

The construction workers are starting to get off their shifts, bending over the slot machines or the bar. Everyone else looks at least a hundred years old besides an exceptionally young, beautiful barmaid in dixie shorts and cowgirl boots. I’m nursing a basket of fried chicken and ranch, washing it down with a Rainier. Finding Rainier in a place like this is like running into an old friend.

TJ, one of the construction workers, offers to buy me a shot. “Just lost my dentures swimming Sue’s pond, y’ know, the older lady sitting here earlier, but I figured I’d go outside my comfort zone and buy a gal a drink.” He’s far too young to have dentures. I go for Hornitos. “Make that two,” he adds. We cheers, his hands still sooty from his job site. I learn TJ is also not from Drummand. He walked here all the way from Arkansas. It took him 40 days and 40 nights with nothing but a guitar, which is an exaggeration but not necessarily a lie.

Since getting off the train, it’s taken me seven by bicycle. I had just moved out of my house in California. I shoved all my belongings into a 5x8’ storage unit save for my bike and camping gear and caught an overnighter from Portland to Whitefish, Montana, during which I drank a gifted unlabeled bottle of wine to myself. Pleasantly drunk with the great Columbia River rolling out the window, me and my friend Nate talked on the phone for hours, about the joys of his ketamine therapy and whether sadness is really the opposite of joy, or just another flavor of it. Nate thinks of it like different keys on the piano, how multiple keys can be pressed at the same time. Like how some of us find a warmth in our sadness and call it melancholy. The call was dropped and I slumped with the wine, satisfied with my newfound freedom but exhausted with the monumental heartache and change of the past few months. I listened to this new piano chord in my heart until I rocked to sleep in the arms of the Amtrak, barreling through the foreign night. I love being on the train; the only direction it knows is forward.

I awoke to an attendant tapping me, “Whitefish in 5 minutes.” I hopped off at 7:00am and took my first ever step on Montana in its smokey dawn. I spent the day swimming in the lake, feigning weightlessness. Lately life has felt like something I’ve needed to carry. I swam 50 yards out to a buoy, feeling the water swallow me. The feeling is whatever you call it, I thought. Instead I let the lake hold me, floating on my back in between the water and the sun, closing my eyes half-way and watching rainbows play on my eyelashes. Back at the hiker/biker campsite I made a fire and sat around with another bike tourist, an older Parisian named Clare. I taught her about s’mores and she wrote the recipe in her notes app.

My bike ride from Whitefish to Big Fork was 50 miles of country roads on what was to be the last day of summer. When I’m on tour my thoughts orbit things like what am I doing with my life, the past, the future, illuminations, ideas, boys, heart break, grief. On a bike they never last too long, everything always circles back to I’m hungry or I’m tired. This is why touring is one of my favorite things to do. I am reduced to a machine with a single purpose. Most afflictions of the human psyche slip away as I become only my body.

I stopped at a Lutheran church on my way to a lakeside campground in Big Fork to refill my water and rest. The woman at the front desk was very excited for me, called me young lady and said things like “oh my buckets” while I sweat all over her lobby chair. She taught me how to talk to a grizzly bear, it’s akin to scolding an ornery toddler.

In Big Fork I stopped at a saloon to settle my hunger before setting up camp along Flathead Lake for the night. The five men at the bar glared at me as I walked in, seeing right through my body hair, septum piercing and stupid alt-girl tattoos. I sheepishly offered my California ID and ordered a beer and gyro. While I ate I listened to one of them launch into a story of the time he tried to pick up a prostitute, walking towards her when another man got there first.

I chose the wrong side of Flathead Lake (biggest lake west of the Mississippi) to bike the next day; winding roads busy with semis and not even a foot of shoulder. In Montana, they put up a white cross at the site of a highway fatality, and Highway 35 was a morbid reminder of my own vulnerability. I weighed the risk of getting hit by a semi and getting kidnapped, and as rain started to fall I stuck out my thumb. 30 minutes later a man in a big truck pulled over and said he was headed to my destination, Polson. I had looked hopeless and normal enough to him; and all the instantaneous calculations made when vibe-checking a person read him as safe.

Ever since having daughters he has been a ‘sympathizer of the female condition’. He told me raising girls was much different; he let his boys go wherever they wanted but the girls were restricted to their neighborhood block. “You packing heat?” he asked, which would become the predictable refrain echoed in most of my encounters with men. I was not packing that kind of heat, which was blasphemous and unimaginable. “You’re brave,” he tells me. I wish it wasn’t brave to exist freely in the world.

He dropped me off in Polson where I biked to my Warmshowers host’s house. These were people I had never met and have barely talked to online but nonetheless let me into their home while they were at work. I had always loved the hospitality of characters in Greek mythology because of how any passing vagabond could be a god in disguise. I’m just a girl on a bike but that’s good enough for some people. They told me to welcome myself to anything in the fridge, do laundry, take a shower, and use the hot tub. The house was warm and decorated with peace signs and boho knick knacks with sweeping views of the Mission Mountains. My guest room looked as if a kid on Extreme Makeover Home Edition said they liked bikes.

I stayed with Doug and Andrea for a few days waiting out the rain and doing work by the fire. They’d make me breakfast and dinner, the latter of which we’d enjoy together like a family and share stories. Our last meal together, Doug told me about the day their daughter was born, how he was so wildly unprepared that he hid out in a tent in Glacier Park for two weeks in the middle of winter, but when he held her for the first time, he couldn’t believe he could love something so much. I involuntarily started crying. Not sobbing, but a quiet stream of tears as I heard him gush about fatherhood. I always felt awkward in normal people’s houses, remembering that family was something to cherish for most. We drank more wine and watched some important baseball game. Doug and Andrea were die-hard Yankees fans and I became one too, adoring all their little mustaches and haircuts. It was very hard to leave.

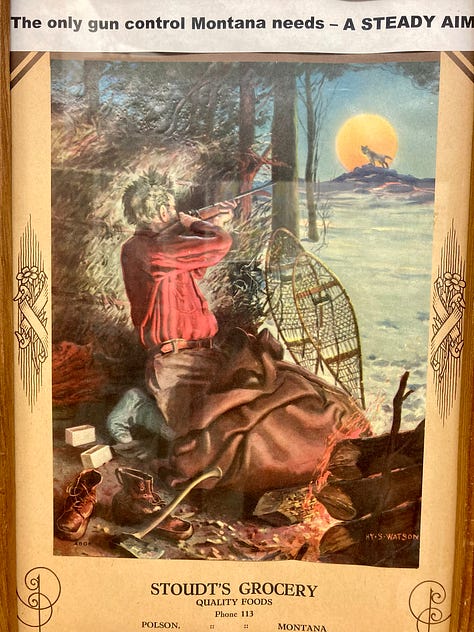

Doug and Andrea lived near the Miracle of America Museum, a labyrinth display of patriotic and industrial jetsam of the past two centuries sprawled across five acres. It smelled like metal and dirt. I sat in a discarded Huey helicopter that’s probably killed thousands of people and ruined many other lives. The button was right there on the clutch like a video game, red and very easy to press: “Trigger Turret Fire”. Tanks, race cars, boats, guns, farm equipment, vintage appliances, barber shop equipment, war rations, literally anything arranged themselves like a procession at America’s funeral. It was a sad reminder of the devolution of our aesthetic morals; how even 70 year old insect repellent packaging was worthy of display on a living room shelf, perhaps next to a candle and a monstera.

Onwards south to Missoula, a town that kept getting me drunk but more importantly, taught me how to swing dance. I had envisioned being spun around by cowboys in tight Wranglers but instead had to settle with college grads with names like Griffin. Unlike California where nobody partner dances unless it’s grinding, even the most banal guys on the dance floor know how to cut a rug. Missoula damn near roped me in, but my life’s purpose had been reduced to riding a bike so I headed east towards the state’s capital, Helena.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned from traveling the states, it’s that I’m a Californian. Nowhere do I feel this more than in New York City or Drummand, Montana; a town of 257 people 40 miles east of Missoula. All of a sudden I’m the only girl in the bar with leg hair saying things like Right on. I had planned to sleep at the local campground, but when I arrived it was a dry empty field save for a boarded up trailer. I elected to stay at a historic hotel.

I was the only guest for the night in this magnificently large and vacant building. Why did we ever do away with tall ceilings, gingham wallpaper, columns and framed archways? My steps echoed infinitely up the wooden stairs. A pair of each men’s and women’s underwear laid scattered atop the landing. The view from my window was a patio littered with beer bottles and at least a thousand cigarette butts. I left early in the morning.

I’ve biked all around the west coast but nowhere has been more helpful than Montana. Doug pulled me over as I was leaving Drummand; offering me a gas station breakfast, a ride all 60 miles to Helena, money even, but he didn’t quite pass the test like my previous ride did. He was extremely worried about me or desperate; either way, I wanted to ride my bike. I didn’t come out here to hitchhike. “Are you packing heat at least? There’s a lot of weirdos out there.” This I know.

At this point autumn had fully descended and more rain started to fall as I entered the most desolate stretches of my trip. I was wet, hungry, and increasingly petulant until the Avon Family Cafe opened its warm arms and Tammy the 60-something year old waitress welcomed me in like I was the world’s orphan. Diners hit like a drug when you’re down n’ out. I sat at the bar and ordered a coffee and two eggs over medium (no diner has ever gotten this right) with hash browns, bacon, sourdough and a huckleberry cinnamon roll – it was like poetry. I read the local paper while Tammy fluttered around, refilling all her cherubs’ coffees. An outfit of camoed hunters ate in the corner talking about their elk kill, one of them her husband.

The Silver State Post had some sobering news to report. At a nearby campground I had considered staying at, a man assaulted his daughter with a weapon and attempted to kill other campers. Another recounted former Phillipsburg mayor charged with possession of drugs and paraphernalia. The diner closed at 2:00pm and I was thrown back out into the rain, without a gun and lonelier than when I came in.

I continued alongside the Little Blackfoot River, its snug valley punctuated by granite rock faces, lodgepole pines and hay farms. The world was wet and shimmered on autumn’s gossamer threads. I stopped at a bar up the road, to wait out the rain some. I sat with a Vietnam vet who was excited to talk about surfing La Jolla in the 60’s after hearing I was from San Diego. It is these conversations that mean everything to me, the ones that aren’t trying to be anything more than reaching out a hand in the dark.

Life has a different set of physics when you unspool from your routine, from the comfortable reality you’ve been fostering at home. Everybody is an angel and everything is a sign when you’re out there in the dark. An older man flagged me down at the base of a steep pass, notifying me of the severe fog descending further up the road and the resulting lack of visibility. He offered to take me to Helena, as he was a local used to driving Continental Divide hikers around during the summer. It was wet and getting late, and another two or three hours of riding to my friend’s house. I resigned myself to the ride and threw my gear in his truck bed.

Bill was 83 years old, a long time writer with a boy-like charm and tortoise-rimmed glasses who spoke didactically, in the way old wizened men do. In the span of thirty minutes he shared the premise of three of his screenplays, told me how he rescued Yellowstone’s Kelly Reilly from a snow storm, his matchmaking of two Continental Divide hikers, his befriending a 75 year old bum who walks the Divide back and forth. The fog surrounded us in thick white sheets, we couldn’t see past ten feet around us. “I'm too old to make my own stories anymore,” he tells me. “I like to be a part of others’ now.”

There’s something about state capitals where they often end up being the least inspiring cities. I stayed with my friend Julie in Helena, working at her apartment together and sharing in her ennui. It felt that the only thing to do was go to trivia nights at the local bars that were shitty and not in a good way. After Helena, I landed on her friend’s farm in Bozeman. They taught me how to butcher chickens, from the slaughter to the gutting, using the jewel-like gizzard to ground me in their innards, still warm with life. I peeled away from the farm one day to go on what was to be the worst Tinder date of my life with the techno-lord of Bozeman, dressed like he’s been awake in Berlin for three straight days. Within ten minutes of meeting him he told me he was suicidal because he cheated on his girlfriend with his ex. A few months ago, his lung also collapsed – turns out you can’t smoke ketamine. Although he was living at his parent’s house he claimed to be too broke to buy a beer so I got him a $3 Montucky. We hung out for one weird hour and I made him drive me home.

I had to get the hell out of Bozeman. Something about it, its urban chrome and sketchy boys. I biked through the Bridger Mountains to the small town of Livingston, the beautiful charming mouth of Paradise Valley. At this point it had been two and a half weeks and 350 miles since I got off the train in Whitefish. Montana had grown to be my friend, and as friends go, it was a place that I could trust.

A virtual stranger sympathizing with my bike tour on Instagram had linked me with Eamon, a 22 year old Deadhead from Queens living with his brother in the valley on the Yellowstone River, who wasn’t unfamiliar with random people sleeping on his lawn. Before we had met he invited me to the cold beverages in the fridge while he was at work. I happily obliged.

Eamon was as tapped in as you could be in a small town. In addition to leading youth backpacking trips, he worked at the historic Murray Bar and hosted a weekly jam night, where I met a wide range of unsuspecting characters that included a model famous enough to have a dozen IG fan accounts, train hoppers, the Scottish lead actor of Braveheart, and a few revered artists and photographers. I talked with a Pittsburgh transplant, a cinematographer who first came through shooting a movie in the area. “Ever since my first time visiting, I knew I was going to live here,” he told me. “I’ve never felt more free in my entire life.” Eamon kept bringing me cocktails and I danced with an 80 year old man in a Dark Side of the Moon shirt who spun me around with 50 years of experience. Still no cowboys in tight Wranglers.

Eamon took me to the Pine Lodge one night, a venue renowned for booking some of the jam and bluegrass scenes’ greatest. It was there where I asked a young man that looked like a Boot Barn model where the bathroom was, who answered in a British accent. It turned out that he and his friend were in America for their very first time helping take care of one of their dad’s friend’s horses. That began a long night of partying around town that ended up with all four of us naked in a hot tub at the multi-million dollar ranch they were staying at, playing the music each of us listened to in highschool off a phone speaker. They didn’t like Sublime.

We had drunkenly made plans to raft the Yellowstone that miraculously materialized the next day despite the earnest hangover that had descended upon our group. It was my first time rafting. The four of us and a cooler of drinks piled into Eamon’s boat and set off on a perfectly balmy September afternoon. I had forgotten all about the previous rain, the threats of snow. The river was flanked by the Absaroka and Gallatin Ranges, mountains that could teach you about time. I wanted to be a valley, held for a million years.

It was comforting to move at the pace of water, like floating on a cloud. “That’s John Mayer’s house,” Eamon pointed at a riverside estate. It turns out the homeowners of Paradise Valley have a combined worth of $290 billion. “PLAY US A SONG, JOHN!” yelled the Brits. Along the bank aspens and cottonwoods shuddered, shaking off their brilliant leaves all around us. We drifted past a golden eagle, perched aside his priceless nest.

This had me captivated, the humor and melancholy and the weird turns of solo adventuring. Great work.

Absolutely mesmerized by your storytelling! She does it again folks!!