A talk with Sight Study

the art of collecting and magic of the mundane

Gabe Schneider, AKA Sight Study, is a 28 year old Northern California based artist blending elements of folk art, textile design, and collage with an illustration and graphic design practice. His commissioned work has a distinct presence in the West Coast poster art world. He’s done album artwork for Jerry Garcia, illustration for The New Yorker, and designed merch for Young The Giant and Pearl Jam to name a few.

Gabe is not only a talented artist but a great friend. We met in his hometown of Arcata, California, a small college town of 14,000 nestled amongst the redwoods on the northern reaches of the California coast. I spilled a drink on his white pants at a party but he still showed me his collection of old radio QSL cards. He loves Corralejo tequila, and is a Lana Del Rey girlie by day, Tom Waits man by night.

Gabe grew up in a creative household with both his parents being artists, his dad having run Humboldt State’s ceramics program after coming up north to escape the mayhem of Southern California. His family’s community of artists and makers always made the arts feel like a viable path. Humboldt County is also the nation’s weed capital. As my ex-con landlord-turned-outlaw country singer croons, “If you live in this country and you ever smoke grass/ You can thank Humboldt County for risking our ass.” Gabe remembers the kids of weed barons counting stacks of cash in class, selling pounds at school, and driving BMW’s. It’s more or less a weird place to grow up, but what he appreciates about it most is the air of cultural and artistic freedom and the multidisciplinary art he was exposed to throughout his upbringing. Oh, and The Logger Bar.

Gabe and I shared a hot cocoa from Cafe Mokka (they have the best whip cream in town) while we talked about the importance of collecting in the creative practice, the magic of the mundane, the power of design, and aesthetic trends in modern poster art and what it says about our generation.

V: When did you start getting involved in the scene and launching your artistic career?

G: I remember getting commissions early on. I would do little band posters for my dad when I was in high school, for his blues band. Then, probably around 2016 or 2017, I did branding for a friend’s skincare company based out of Petrolia. She was growing all her own herbs and turning them into various skincare products. That was one of the first times I had a big branding project to really sink my teeth into. This was before I knew I wanted to go into graphic design or illustration, or where my career path was going to take me. And from there, I feel like I just started to pick up more and more gigs as time went on.

V: So when did you start transitioning into doing a lot of music industry stuff? Your art feels like it’s a part of this new era of West Coast concert posters.

G: I've always been really attracted to poster art as a craft. I've always loved the iconic design of posters from the 60’s and 70’s. I think I first started getting into it seriously around 2019-2020 when I did some work for Andy Cabic of Vetiver. I ended up doing a poster for him, which was a dream come true as a longtime fan. It was really exciting to take what had been a long personal practice of illustration and design and turn it into something functional.

After the work with Vetiver, I got a job with Woodsist, the guys from Woods, for the festival they put on and their touring company. From there, it just grew, thanks to Instagram, which can be a fickle tool but is also necessary these days. It allowed me to connect with more and more artists that I really admire and love.

V: 60’s poster art was defined by psychedelic art nouveau. What do you feel are the aesthetic trends of our current era? Because honestly, poster art says so much about a generation.

G: I feel like we're in a place where it's hard to define a single trend because unlike the 60’s where there was a clear common thread with artists tapping into art nouveau influences fusing with the rise of psychedelic rock, today's design trends are more of a melting pot of influences, similar to how music genres have diversified. When it comes to poster art, I think it mirrors that diversity of genre—there's just so much out there.

There's been a lot more independent artists and designers being commissioned for their unique styles, and these artists might not necessarily come from a graphic design background. They could be fine artists applying their styles to poster art. So if there's one trend, it's the widening of what is considered poster art, allowing for a resurgence of a broader variety of artists to enter what was maybe temporarily a more corporate-dominated field.

V: Your art reads as a collage of everyday mundane objects, infused with a modern take on art nouveau and folk art. I’ve seen you incorporate squirt bottles, your watch, cans of Rainier, yo-yo’s, a friend’s Volvo station wagon to name a few motifs. What role does collecting play in your practice?

G: Collecting definitely plays a huge role in my work. Before I got into illustration, I did a lot of mixed media/collage. My dad is an assemblage artist, and I remember him going on runs when I was a kid, picking up garbage from the side of the road, bringing it home, and putting it in these crates that now fill his whole studio. I think that collector’s mentality rubbed off on me.

I also remember being a kid and visiting the homes of my folks’ friends. They were all artists too, and their houses were like walking into natural history museums, filled with these amazing collections. You’d see everyday objects or parts of machines you might not even recognize, but they’d be on display like little art pieces. Just taking these objects out of their usual context and putting them in a different space made you see them in a new way. I remember looking at them with this total curiosity, and that’s something I always try to bring into my own work.

What I find exciting is bringing that collage mindset into my illustrations. When I moved away from mixed media and started doing more illustration work, I wanted to keep that same approach. I’m always picking up little things—sights, sounds, objects—and weaving them together. Even though my work now is more 2D, I like to keep that same kind of energy, recontextualizing the mundane to help people see it in a new way.

V: The beginning of every art practice is awareness, and a sense of connection. I feel like collecting can be a means of creating a personal mythos and symbology.

G: Yeah, I think that’s a really interesting idea. I don’t think I ever set out to explicitly tell my story through my work, but I think it happens naturally. It’s like if you send anyone out into the world for a day and ask them to take pictures of what catches their eye, everyone’s going to come back with something different. That personalization is really exciting to me. The things I go out and ‘collect’, so to speak, are unique to me. You know, like the squirt bottle, the Rainier can, or my gold Casio watch—these are all things that have a specific meaning to me. But it’s all about who’s doing the collecting.

I’m not a very extroverted person, and being a personality on social media doesn’t come naturally to me. But through my work and the things that creep into it, I’m able to share bits of myself that I might not outwardly share otherwise. It’s like you get to see what catches my eye and learn a little more about me through that process. I think there’s something valuable in that.

V: The way you incorporate these motifs with your iconic color palette and ornamental flourishes feels like you're placing these everyday objects on an altar.

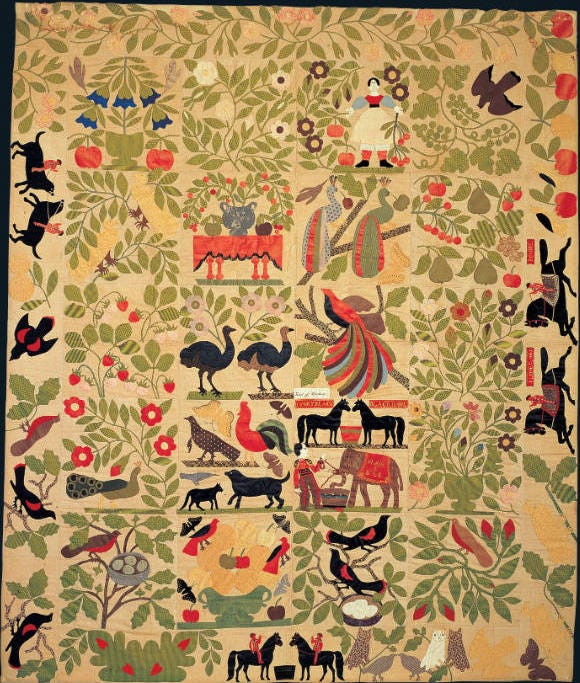

G: I’ve always been really drawn to folk art and religious art, and these design practices that utilize these super ornamental compositions. They’re beautiful on their own, but they also use intricate designs to communicate the importance or divinity of certain objects, portraits, photographs, or even poems. That idea of using design to convey significance, while also connecting it to this really old aesthetic tradition of folk art, has always been super compelling to me.

These pieces can feel truly altar-like, just like you said, where the design itself seems to be honoring whatever it’s framing. I’ve always loved combining that idea with the art of collecting. It’s like creating your own Cabinet of Curiosity or altar, where you go out, gather these objects, and then bring them home to display and organize them in a way that feels meaningful to you. I love collecting these objects and moments—whether it’s through photography, video, or illustrations in my journal of little things I see—and then tapping into these age-old, ornamental design influences to highlight the importance, the divinity, or the mystery and magic of what might otherwise be seen as mundane objects.

V: It really is a testament to how observation is the beginning of any creative practice. If you’re not in awe you're not paying attention.

G: Observation is everything. I’ve always seen art as a way of processing all the stimuli you gather throughout the day. When I was really into photography, after a while, you start seeing everything as a photograph. You begin to notice the beauty in the mundane because you’ve retrained your eye to see the world with this soft, nonjudgmental gaze.

That’s something I try to encourage in my own work, both for myself and for the viewer. To find inspiration for my creative practice, I need to just observe. I need to let my guard down and go look at things. A big part of my process is going for walks and just seeing what I see—even if there isn’t an end product in mind. If I’m stuck creatively, that’s what helps get me out of it—just going out and looking around.

I think that’s key to any creative process. If you’re cooped up in a studio or an office, trying to force yourself to create without any new input or stimuli, nothing’s going to happen. It’s also a huge form of meditation for me. I’ve never been one for traditional meditation; my mind tends to run wild. But I’m a pretty anxious person, and one of the things that helps the most is going out and seeing the world in a nonjudgmental way. When you do that, I think you really start to see the art in everything. It’s all about observing, and that’s been one of the biggest aids for me in working through different mental health challenges.

I think it’s super helpful for the anxious mind. As soon as you start to find the art in everything, everything becomes art. And when everything becomes art, all these barriers drop, and the whole world becomes easier to process and comprehend—creating a softer world to live in.

Good article 😎

Really enjoyed this interview and more background on Gabe‘s work, Velen! Thank for for writing this! Good questions and great insight into the Site Study works and inspiration! So nice to read.

I just went and saw Vetiver last night on Mill Valley and was pretty thrilled to be able to buy one of the Site Study posters Gabe made for the show!

Also very fun coincidence, I went to HSU (pre- Poly) in the late 90’s and fell in love with Arcata, living there for five years and truly love the unique area up there. Happy to have found your substack!!